Who is Brooklyn for?

Brooklyn is the heartbeat of New York City; its soul has been vanishing all our lives

“The film is about amplifying community voices in Brooklyn,” she says. The black frames of her glasses match her tied-back hair and fit her face perfectly. It’s a face of character and depth. As she speaks, she exudes a calm, steady confidence somehow enhanced by her New York accent. It makes everything she says instantly compelling. She’s effortlessly charismatic … and doesn’t seem to realise it. Everything about Alyssa J. Wilson draws you in.

Alyssa is Brooklyn born and bred; a native New Yorker without the ego but all the pride. She was born at the Methodist Hospital in Park Slope and raised in Prospect Heights, where brownstones and tree-lined streets greeted her at every turn. She grew up with her parents and five younger siblings, surrounded by a village of aunts, cousins and grandparents.

She wants to remain in that place she has always called home, but has seen too many people leave the area because they’ve been priced out. She fears that she will be next in joining that exodus. “If I want to buy a two- or three-bedroom condo in Prospect Heights, say 1,200 square feet, I would need to get a mortgage of two million dollars or more … it’s just not realistic.”

Alyssa is an independent filmmaker who is turning her attention to the story she has long known she needed to tell. She’s working on a documentary – provisionally entitled Seen – that shines a light on a growing sense of alienation among many of Brooklyn’s long-term residents. They see their neighbourhoods becoming increasingly transient and feel at best overlooked and disregarded, at worst like they are an inconvenience getting in the way of newcomers to the borough. They grapple with their feelings of resentment towards the new arrivals, who seem only to want to bend Brooklyn to their own tastes rather than blend in.

Alyssa speaks fondly about the influence Spike Lee’s Crooklyn had on her, having first watched it as a five-year-old. She tells me how Troy, the film’s young protagonist, felt like a reflection of herself. The film’s street scenes appeared as a mirror image of her own brownstone upbringing; its characters reminding her of people she knew intimately. “It’s like Spike Lee said: Brooklyn is not just a place, it’s a state of mind.”

The reality is that the Brooklyn Alyssa was born into has been steadily disappearing all her life. Mention Brooklyn today and most of us would probably picture a post-industrial landscape with any combination of hipster cafes, yoga studios and – of course – expensively restored brownstone townhouses; and all connected to demographic changes in the local population.

What I’m describing here is commonly understood as ‘gentrification’. I’m hesitant to use the term without an explainer because, like so many everyday concepts, the more you delve into it, the more you learn that its meaning has adapted over time. The word itself is derived from ‘gentry’, a term used historically in Britain to describe people of high social class just below the nobility. To ‘gentrify’ is to make something more refined or genteel; that is, suitable for the gentry.

The ‘gentrification’ term was first coined in 1964 by sociologist Ruth Glass, who founded the Centre for Urban Studies at University College London (UCL: a place where all the best people study!). She employed the concept of gentrification to describe social trends occurring in parts of London, where working-class neighbourhoods were being transformed by the influx of middle-class residents. Glass wrote:

One by one, many of the working-class quarters of London have been invaded by the middle classes — upper and lower. Once this process of 'gentrification' starts in a district it goes on rapidly until all or most of the original working-class occupiers are displaced and the whole social character of the district is changed.

- Ruth Glass, London: Aspects of Change, 1964: xviii–xix

Of course, the term ‘gentrification’ has since become widely used in everyday language. Most of us understand it with a negative connotation: it describes displacement, cultural erosion and inequality. This is how I’m using it here. For anyone interested in delving deeper, I found this paper useful.

Ask any New Yorker about Brooklyn gentrification and most would tell you that it all started in the 1990s, when Alyssa was born, before ramping up in the early years of this century. Well, the second part is certainly true. However, the trend was set a few decades earlier than many of us might realise.

In his book, The Invention of Brownstone Brooklyn, historian Suleiman Osman illuminates how gentrification in Brooklyn neighbourhoods like Park Slope and Fort Greene actually has its origins in the 1960s and 1970s. And it wasn't just about rising rents or real estate markets; it was a cultural project, led by (largely white) middle-class professionals seeking 'authenticity' through community living and connection to a romanticised past.

Osman focuses on the post–World War II period up to the 1980s, prior to the full-blown gentrification waves of the 1990s and 2000s that has provided the backdrop to Alyssa’s life. His book lays the groundwork for understanding how cultural, political and social shifts in the mid-20th century invented a new vision of urban living that continues to influence Brooklyn life today.

Osman's work challenges us to rethink what drives neighbourhood change; and who gets to define what a neighbourhood is supposed to be.

As I touched on in a recent piece entitled The Right to Bed-Stuy, the reshaping of Brooklyn can be viewed through the lens of what philosopher and sociologist Henri Lefebvre termed the production of space. Lefebvre argued that space is not neutral or passive, but actively produced by social, economic and political forces. In Lefebvre’s analysis, urban space becomes a commodity, consumed and controlled by those with capital, stripped from those whose lives once animated it.

From Dumbo to Bushwick, Williamsburg, Bed-Stuy, Prospect Heights – you name it, we are witnessing this transformation: warehouses long ago reborn as luxury lofts, graffiti overwritten by branded street art advertising, public life privatised. What was once a patchwork of working-class enclaves has become the terrain of developers, tech workers and creative class migrants.

In Brooklyn, rezoning policies and speculative investment serve as mechanisms for what urban sociologist Neil Brenner calls urban restructuring, displacing vulnerable populations to accommodate capital flows. In this context, Brooklyn is not just a NYC borough, but also a battleground between competing spatial forces: everyday life pitted against profit.

Anyone with a few million dollars burning a hole in their pocket could try typing “Brooklyn Brownstone” into the Youtube search bar to discover one way of spending it. There they will encounter some glossy videos of realtors impersonating daytime television hosts, marketing the revitalised brownstones that once housed a very different experience of urban living. It has been fading from view for decades but hasn’t – yet – completely been erased. Beyond the ‘bougie’ dream pitched to us via Instagram photos and lifestyle magazines, there lies another Brooklyn; a place of people who are unseen.

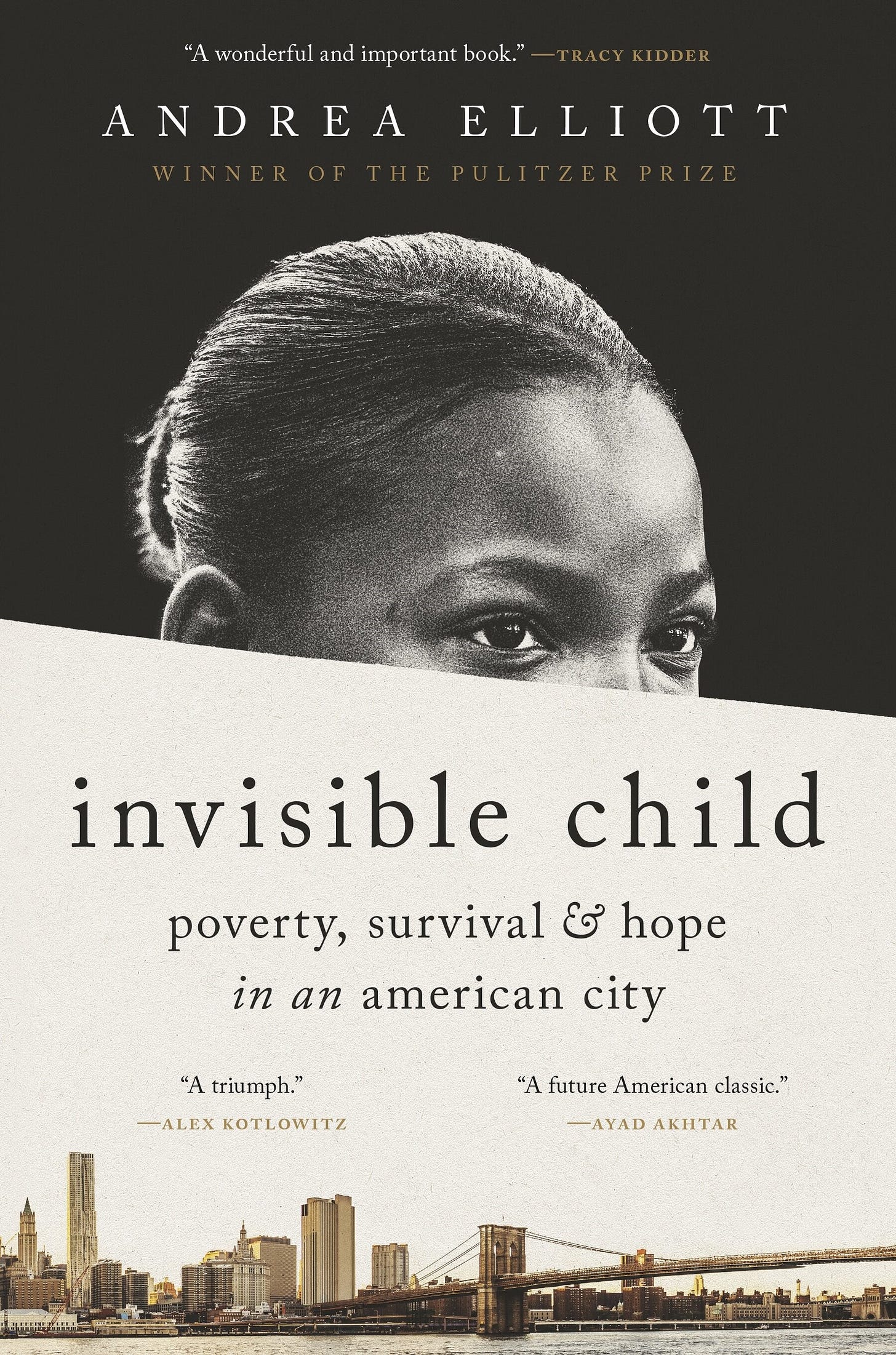

We can acknowledge these people, if we care to. In her book, Invisible Child, journalist Andrea Elliott shines a light on the Brooklyn beyond the brochures. I read Invisible Child three years ago and haven’t read anything that impacted me so profoundly since. The book provides a portrait of structural, generational poverty in America in the most effective way possible: through the lived experience of real people.

Elliott uses the same narrative tools as a fiction writer to shine a light on a girl – Dasani Coates – and her family, trapped in NYC’s brutally demeaning homeless shelter and wider welfare system. Dasani spent much of her childhood at the Auburn Family Residence shelter in Fort Greene, about a mile from where Alyssa J. Wilson was raised. In the book, headline statistics together with an account of institutional failure are woven into a compelling human story.

It is striking how persistent inequality and institutional failure is so easily obscured by narratives of urban renewal and regeneration; how gentrification and systemic, generational poverty can coexist, literally side by side. Dasani’s childhood experience, like so many others in Brooklyn, exposes the myth that a ‘rising tide lifts all boats.’ Rather than focus on those floating high on YouTube, we should give more attention to the sunken lives of those drowning as wave after wave of gentrification laps over them.

Here once more we can turn to Henri Lefebvre for guidance. He introduced us to the concept of the right to the city, producing both a critique of modern urban life and a call to action. The right to the city is not merely a right to inhabit urban space; it is a right to participate in shaping it. Urban geographer David Harvey builds on Lefebvre:

The right to the city is, therefore, far more than a right of individual or group access to the resources that the city embodies: it is a right to change and reinvent the city more after our hearts’ desire. It is, moreover, a collective rather than an individual right, since reinventing the city inevitably depends upon the exercise of a collective power over the processes of urbanization. The freedom to make and remake ourselves and our cities is, I want to argue, one of the most precious yet most neglected of our human rights. How best then to exercise that right?

- David Harvey, Rebel Cities, 2012: 4

In Brooklyn, this right has been denied to many of its long-term residents, particularly Black and brown communities whose cultural legacies shaped the borough but now find themselves priced out, pushed out, almost forgotten.

These dynamics are not accidental. They are products of deliberate urban policy: rezoning (and “upzoning”), tax incentives, and infrastructural improvements geared not toward existing residents, but toward a new demographic that is wealthier, more transient and, yes, whiter.

The new build apartments that sprout up across the borough aren’t intended to be homes for working-class or even middle-class families. They’re designed and priced for professionals – the age profile of whom is rising – who don’t mind sharing space. This building policy exacerbates a predatory rental market, where landlords capitalise on people’s desperation just to remain living in Brooklyn.

And yet, Brooklyn resists. From Crown Heights to Flatbush, urban social movements rise up to contest this spatial assault. In tenant meetings held in community halls, in protest marches that reclaim streets and in murals that remember erased histories, communities assert their right to remain. Organisations like Equality for Flatbush and the Bushwick Housing Independence Project challenge evictions, document abuses and demand accountability from landlords and city officials alike.

These are not merely protests, but have the potential to be acts of urban creation; perhaps even a form of insurgent urbanism. Away from the spotlight of media presented to us to consume, there exists overlooked movements of people seeking to remake the city in more just and humane ways. In Brooklyn this insurgency is attempted, in part, through community land trusts, housing cooperatives and mutual aid networks designed to protect people, not profit.

Such resistance is central to the ongoing struggle over urban space. We need a new politics of urbanisation that places collective need over private gain. In Brooklyn, such a politics can be asserted through every food co-op, every housing court protest, and every block association meeting fighting to preserve rent-stabilised apartments.

Community-based urbanism in Brooklyn can reclaim space not just for housing, but for memory, dignity and culture. This can be spatial justice in action; an effort not only to survive in the city, but to redefine it.

I have an unlikely affinity with Brooklyn. My son was born at University Hospital at Downstate, near Prospect Park. My Puerto Rican uncle came of age in Bedford-Stuyvesant during the 1950s and 1960s. Some of my dearest friends settled in Dumbo two decades ago, transforming a former warehouse loft into a home where they raised their children and built a business. Just around the corner from their old redbrick building, crowds now gather daily for one of the world’s most ‘Instagrammable’ shots on Washington Street, with the Manhattan Bridge rising majestically in the background.

For me, a trip to Brooklyn feels almost like a pilgrimage. From across the Atlantic, I often find myself yearning to return to those brownstone avenues shaded by honey locust and Norway maple, where the air carries the breath of history. There, under a canopy forever autumnal in my mind, the past and present entwine like roots underground. Messy, tangled, inseparable. Each sidewalk hints at details for a story: the cracks in the pavement, the scent of rain on stone, the muffled bassline pulsing from a passing car. The air feels always thick with possibility, yet tinged with the melancholy of constant transformation. New businesses. New money. New people. And still, amid the churn, the spirit of those magical streets endures; a resilient heartbeat rooted in the brutal, complex history of the American story itself. Brooklyn is ever-changing, yet – at least for now – anchored in its identity.

For years now, a question has hung heavy in the air: can Brooklyn remain a home for the very people who gave it its soul? I believe the answer can only be yes if we commit, urgently and intentionally, to telling the stories that lie beyond the polished veneer of 21st-century Brooklyn; if we amplify the voices too often ignored and illuminate the lives that exist in the shadows of brownstones and new developments alike. This is the work Andrea Elliott did so powerfully in Invisible Child; bearing witness with compassion and precision. It’s the work that Alyssa J. Wilson and I myself are trying to continue; insisting that Brooklyn’s full story be told, not just the parts that fit neatly into real estate ads and curated social media feeds.

Policymakers and elected representatives respond to the above question with gestures that tinker around the edges of the challenges Brooklyn and other places like it face. We see tokenistic measures seemingly aimed toward equity: mandatory inclusionary zoning; extended rent regulation; and investments in public housing. But these measures always seem to fall short, either in scale or, frankly, sincerity. What is needed, as Lefebvre and Harvey have showed us, is not merely reform but a reimagining: a new urban contract rooted in justice, participation and solidarity.

This means listening to voices of Brooklyn’s unseen people. It means learning the lessons from real-life stories like that of Dasani Coates and her family. It also means treating space not as a commodity to be flipped and profited from, but as an essential public good we each have a legitimate claim to; a commons to be shared.

Brooklyn is so many things, including a metaphor for the tensions and contradictions of modern urban life. It is at once a borough reborn and bereft, revitalised yet ravaged. “It’s like a form of colonisation rebranded,” Alyssa tells me. “We are losing a lot of our cultural pillars, our black third spaces – so many I’ve lost count. Just recently, for example, we’ve lost Bed-Vyne and Lover’s Rock on Thompkins Avenue in Bed-stuy.”

In those glorious brownstone avenues, we see both the promise of urban paradise and the price of free-market fundamentalism packaged as progress. As we contemplate the continued waves of transformation across Brooklyn and beyond, the personal narratives we embrace matter just as much as public policy initiatives. The cultural considerations matter just as much as the economic. Let’s talk about who gets to shape the city … and who gets left out.

I’ve joined forces with Alyssa J. Wilson to do just this; to work on a documentary film that tells the story she and many others have been living throughout the 21st century and before. The film poses a question: Brooklyn is the heartbeat of New York City, but what happens to its soul when the very people who gave it life are pushed aside?

Meeting Alyssa truly was, as the expression goes, a meeting of minds. We bonded over a shared belief in the power of human-centred storytelling; a shared conviction that stories change people, ideas alone don’t. Please stay tuned as we work together to deliver the Gridlocked mission: to see a more equitable world operating sustainably to ensure that future generations can inherit viable societies on a liveable planet.

Sometimes saving the world starts at home, right from our doorstep. For Alyssa J. Wilson that is, naturally, a brownstone stoop.

References:

1. Brenner, Neil. (2019). New Urban Spaces: Urban Theory and the Scale Question. Oxford: Oxford University Press

2. Elliott, Andrea. (2021). Invisible Child: Poverty, Survival & Hope in an American City. New York: Random House

3. Glass, Ruth. “Introduction.” London: Aspects of Change, edited by Ruth Glass, Centre for Urban Studies, University College London, 1964, pp. xviii–xix.

4. Harvey, David. (2012). Rebel Cities: From the Right to the City to the Urban Revolution. London: Verso Books

5. Harvey, David. "The Right to the City". New Left Review, 2008. II (53): 23–40.

6. Lefebvre, Henri. (1991). The Production of Space (translated by D. Nicholson-Smith). Cambridge, MA: Blackwell

7. Lefebvre, Henri. (1968). Le Droit à la ville (2nd ed.). Paris, France: Anthropos

If you liked this essay, you might enjoy these related pieces:

The Right to Bed-Stuy

It’s an unseasonably hot autumn day, about 25 degrees Celsius. I turn from Franklin Avenue onto Hancock Street, hugged tight by imposing four-storey Italianate brownstone terraces that frame each side of the road. Stoops worn smooth by decades of hard footsteps on soft sandstone seem to whisper secrets from a storied …

Nightswimming

My arms make arcing breaststrokes in tepid turquoise water, slicing through its smooth thickness which envelops my skin like silk. I bob down 15 feet or so to the seabed, where the water turns darker blue, cold, invigorating. I pinch my nose as I twist my body to look upwards at the light above. As a child I feared the salt stingi…

Another fantastic read! You broke down what’s happening in Brooklyn and a way to chart a path forward so eloquently. I can’t wait for the film!

Grateful to be collaborating with you through Seen and beyond!!