Nobody Understands Climate: Can We Trust the Science?

The Anthropocene Essay: Part Two of Three

… this essay continues from Part One: “Nobody Understands Climate: Kerry Emanuel and Hurricanes”

No matter how many graphs you draw up, as long as they are graphs about the future they don’t necessarily hold any more water than a leaky boot.

- Margaret Atwood

When people say they “trust the science,” what they presumably mean is that science is rational, empirical, rigorous, receptive to new information, sensitive to competing concerns and risks. Also: humble, transparent, open to criticism, honest about what it doesn’t know, willing to admit error.

- Bret Stephens

One of the key international policy responses to human-caused climate change came when 196 nations committed to limiting global temperature increases, when they gathered at the United Nations Climate Change Conference (COP21) in Paris in December 2015. The specific pledge was to restrict Earth’s temperature to “well below 2 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels,” and aim to “limit the temperature increase to 1.5 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels.”

The UN’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) indicates that crossing the 1.5 degrees Celsius threshold risks unleashing far more severe climatic events, including more frequent and severe droughts, heatwaves and rainfall. Since then, many governments have stressed the need to limit increases to 1.5 degrees Celsius by the end of the century, and many have announced “net zero” policy targets for the middle of this century. As I will come on to discuss, this is all likely to be too little, too late.

Before getting into the level of progress being made to meet climate targets, it’s worth touching on how confident we can be in what the data is showing because some people still dispute it. Whilst the data is robust, dealing with the question of climate science denial is important – though I will only do so very briefly, because it doesn’t deserve too much oxygen.

Ignoring incontrovertible evidence is irrational. In the case of climate science denial, it tends to be driven from ideological dogma fuelled by disinformation, often to serve the special interests of the fossil fuel industry. The subject is well covered and refuted elsewhere and, as I say, I don’t wish to give it much energy (no pun intended).

Doubt, however, is different from denial. Doubt can be reasonable; scepticism is an intellectually healthy position to start from – that’s why I included Margaret Atwood’s advice above. Scepticism is where any scientist worth his or her salt starts from their research.

So, even though we can ‘trust’ climate science, let’s assume for a moment that we aren’t certain that it is accurate enough. If we have lingering doubt, then we need to think about risk and taking chances. Here I defer again to the wisdom of Kerry Emanual, MIT Professor Emeritus of Atmospheric Science, who discussed this point when interviewed for the Gridlocked podcast:

“We are taking a risk, the tail of which is an existential risk … Let’s say you had a seven-year-old daughter and she’s a bit late for catching the school bus. If she misses it, you’re going to have to drive her to school and you’ll be late for work. The school bus is across the street and she can make a run for it. The problem is, you calculate there’s a five percent chance she’ll be run over and killed. It’s a small chance, but you won’t do that because the consequences of losing her are way, way worse than the consequences of you getting into trouble for being late for work. So, it’s a no brainer, nobody in their right mind would let that child run. Well, the problem here is that there’s somewhat larger than a five percent existential risk to civilisation if we don’t do anything about climate change and lots of scenarios have been painted. It doesn’t take a lot of imagination: food and water shortages have historically led to armed conflict. That can happen again, but now it’s happening in a world armed with nuclear weapons.”

The challenge with climate change politics and policymaking isn’t a lack of evidence, inconclusive data, or scientific disagreement (which may exist on some points, but isn’t the major roadblock). The issue, to my mind, is an information/ public communication problem.

The challenge is how to talk about climate science and deal with the concept of “existential threat” in ways that resonate to the everyday lives of individual citizens, whilst at the same time mobilising governments, international organisations, corporations and wider civil society to act collectively to bring about change … with the (collectively expressed) consent of those individual citizens.

This requires trust. Scientists tend to be highly trusted, while politicians and energy companies are viewed with considerable scepticism. Important climate discourse has been made more challenging in this so-called “post-truth” era, in which some believe we can simply invent our own “alternative facts.”

The second quote I opened this essay with is from a New York Times opinion piece written by Bret Stephens, entitled, “The Mask Mandates Did Nothing. Will Any Lessons Be Learned?” It elicited a strong response in the paper’s letters section the following day.

I don’t wish to discuss the specifics of mask mandates, or the merits of the writer’s criticism of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) adherence to its masking guidance. I was, however, struck by a broader point Stephens made in his piece, when he wrote of the CDC: It isn’t merely undermining the trust it requires to operate as an effective public institution. It is turning itself into an unwitting accomplice to the genuine enemies of reason and science – conspiracy theorists and quack-cure peddlers – by so badly representing the values and practices that science is supposed to exemplify.

When we consider this, science communication – already imperative – takes on an additional significance. If the COVID pandemic taught us nothing else, it demonstrated that how we communicate important public health information, based on medical science, can profoundly impact so many aspects of our lives that we take for granted … whilst, of course, making the difference between life or death on a large scale.

At the same time, COVID showed us that science communication does not operate in a vacuum, but is just as exposed to political and social division and interference as other fields of our public discourse. Climate science is no exception.

The story of climate change is one of competing narratives, including narratives within narratives between those who agree on the central question of human activity being responsible for the significant increase of temperatures since 1950. We should focus on the observed reality: we are witnessing increases to the frequency, intensity and extent of extreme climate change events – from devastating floods, droughts and heatwaves, to hurricanes like the one Philip Gerard wrote about.

Gerard’s personal essay provides human context to scientific evidence, such as the research led by Kerry Emanuel:

My colleagues and I have shown that hurricanes should become more intense and produce much more rain as the planet warms, and observations are beginning to show such trends. The 2005 Atlantic hurricane season was the most active in the 150 years on record, corresponding to record warmth of the tropical Atlantic. Katrina, which caused the largest storm surge in US history, cost more than $200 billion, and it claimed at least 1,200 lives. The 2017 Atlantic season was among the most destructive on record, causing well more than $300 billion in damages. The all-time record wind speed in a tropical cyclone was set by Typhoon Haiyan in 2013, only to be broken by Hurricane Patricia in 2015. Hurricane Sandy of 2012 had the largest diameter of any Atlantic storm on record, and 2017 Hurricane Irma set the world record for sustained Category 5 intensity, while Hurricane Harvey – in the same month – produced more rain than any hurricane in US history. Globally, tropical cyclones cause staggering misery and loss of life. Hurricane Mitch killed more than 10,000 people in Central America in 1998, and in 1970 a single storm took the lives of some 300,000 in Bangladesh. Substantial changes in hurricane activity cannot be written off as mere climate perturbations to which we will easily adjust.

- Kerry Emanuel, What We Know About Climate Change, 2018: 39-40.

Some climate scientists are making bolder assertions than others. On 24th June 1988, the top story on the front page of the New York Times late edition was entitled, “Global Warming Has Begun, Expert Tells Senate.” The article by Philip Shabecoff reported: Until now, scientists have been cautious about attributing rising global temperatures of recent years to the predicted global warming caused by pollutants in the atmosphere, known as the “greenhouse effect.” But today Dr. James E. Hansen of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration told a Congressional committee that it was 99 percent certain that the warming trend was not a natural variation but was caused by a buildup of carbon dioxide and other artificial gases in the atmosphere.

Almost 40 years on, James Hansen’s testimony to the Senate Energy and Natural Resources Committee is viewed as a turning point in history. Nowadays, as Director of the Climate Science, Awareness and Solutions Program at Columbia University, Hansen is still making headlines – by making assertions that many of his scientific peers are reluctant to endorse.

Hansen’s broader argument that global warming is happening much faster than our aggregated climate models predict is not formally accepted. In 2023 he was part of a group of researchers who produced a study showing that the 1.5 degrees Celsius temperature increase on preindustrial levels threshold could be exceeded this decade. Additionally, they concluded that a 2 degrees Celsius increase will be seen before 2050 (unless rapid decarbonisation beyond current plans is enacted).

Hansen is also breaking from many of his climate science peers by arguing that the rate of global warming is accelerating. This point, together with some of the headline results of the study – namely on the 2 degrees increase and the extent of further increases, together with the extent to which climate change is explained by greenhouse gases – is disputed by other scientists. However, most agree that the 1.5 degrees Celsius target is effectively certain to be missed.

The fact that Hansen has been proved right in the past doesn’t, of course, mean he must automatically be believed now. A consensus of experts is usually more reliable than any one expert alone, though Hansen’s track record suggests that it might be foolish to dismiss him.

Besides, I’m deliberately not going to be drawn too much here on the specifics of disagreements between climate scientists because I am neither suitably qualified, nor do I actually think it substantively matters, in a sense. We are already observing devastating climate change impacts, faster than previously predicted, that require us to act now.

Some scientists are suggesting that it could take the best part of a decade to resolve their disagreements on the rate of climate change acceleration. However, in making climate policy interventions we don’t have the luxury of spending the next few years eagerly awaiting the outcomes of these scientific debates, the conclusion of which would likely come too late to act upon. The danger is that those with competing data sets will continue to bicker, whilst the proverbial Rome burns.

We need to put in place robust plans that are sufficiently flexible so as to be adapted in tune with the changing scientific picture. Even leaving the climate data aside for a moment, we could consider taking a “no-regrets” approach to climate change. Estimates vary at somewhere between 5 to 9 million people – the World Health Organisation puts it at 6.7 million – dying prematurely each year, around the globe, from inhalation of particulates from fossil fuel combustion. The value of those lives alone might justify a switch to carbon-free energy if it is sufficiently cheap.

There is also the problem that current gas and oil reserves are expected to be depleted before the end of this century, assuming current rates of consumption (when in fact consumption is rising and shows no sign of abating). In practical terms, we will likely be forced to get off oil and gas anyway. So, better to pursue a sensible risk-based approach which takes into account the scientific modelling (and different scenarios) and adds in the observable reality of increased severe weather events and the rising price tag associated with them; the costs already being paid.

The purpose of using means in climate data is to establish trends. The global data can aggregate means and/ or mean methodologies, to try to establish a common framework. This is, crudely speaking, what the IPCC does when it produces its summary reports on climate science every few years; the most recent being its Sixth Assessment Report (AR6) published in 2021, with the final synthesis in March 2023 (IPCC’s Seventh Assessment Report is currently in its assessment cycle).

However, using means to predict systemic behaviours can be problematic since the items of particular interest are the outliers and upper boundaries, rather than the means. These are the extreme weather events that cause such devastation.

So, I suggest there is a different perspective we can take, in addition to the good work from the IPCC. We could focus more on the merit of specific, destructive impacts. Temperatures have been increasing, and the increase rate likely accelerating. Extreme weather is getting worse. Increasing weather severity combined with demographic shifts show that the event cost is rising exponentially regardless of whether radiative forcing is accelerating; in other words, regardless of the above-mentioned scientific debates.

The last two years, 2023 and then 2024, were each the warmest on record. The annual average global temperature approached 1.5 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels, which is the target limit established through the Paris Agreement.

Whilst scientists are more concerned with averaged multi-year data rather than one year alone, as mentioned above, the growing consensus is that the averaged data clearly points to us being off-track in limiting global warming. One consequence – among many – of rising temperatures is glacier and ice sheet melting, which is raising sea levels. Another is increased weather volatility, including more severe hurricane activity.

Major population centres and infrastructure assets tend to be clustered in coastal locations (there are large upward trends in both). Increasing coastal population and infrastructure along with rising sea level and increased storm intensity are leading to large increases in damage.

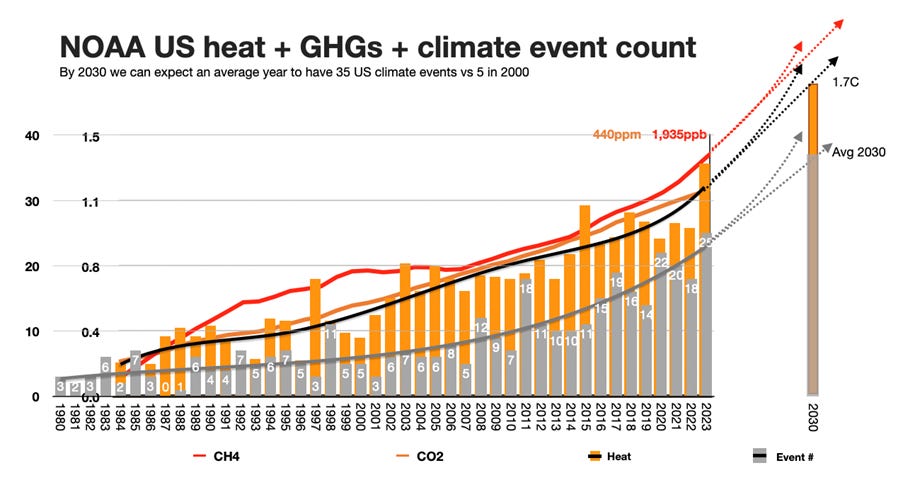

In the United States alone, 2023 witnessed 28 separate catastrophic weather events, each costing more than $1 billion, surpassing the previous record – 22 in 2020 – for the highest number of billion-dollar disasters in one calendar year (using data adjusted for consumer price index inflation). The price tag for 2023 was at least $92.9 billion … just for the United States alone.

The following year, 2024, saw one fewer catastrophic $1 billion event but still surpassed all records prior to 2023. However, 2024 included Hurricanes Helene and Milton and saw the cost of the damage at approximately $182.7 billion (again, just for the U.S.). This places 2024 as the fourth-costliest on record, trailing 2017 ($395.9 billion), 2005 – the year of Hurricane Katrina – ($268.5 billion) and 2022 ($183.6 billion).

Research highlighted by the World Economic Forum estimates that climate change could be costing the world $16 million per hour and that the global cost of climate change damage will be between $1.7 trillion and $3.1 trillion per year by 2050. This might be a conservative estimate: my colleague Rob Freda, a hydropower entrepreneur and MIT Research Affiliate, calculates that we will reach the upper end of that scale by the end of this decade.

So, we can disagree on politics and we can dispute the interpretation of data. However, when extreme weather is already destroying communities, causing fatalities and displacing people, and running up an ever-increasing bill, the debates can seem detached from reality.

We can think of climate change another way, as Kerry Emanuel put it to me:

“We are incurring costs from increased damages owing to sea level rise, increased level of storm activity, heat stress and so forth. The thing that we really need to focus on are what I call the tail risks, and we should be prepared to spend, if we have to, a lot to avoid them. That’s what we would do if it were a short-term risk that’s immediately apparent, like the kid running for the school bus. The psychological problem is that the risks are evolving more slowly in time so we tend to say ‘oh let’s put it off’ … but you can’t do that forever.”

… to be continued next week in Part Three: “Nobody Understands Climate: How Can You Mend a Broken Heart?”

References:

Atwood, Margaret, “Blind Faith and Free Trade”, The Case Against Free Trade, 1993: 92.

Ejaz et al, “How We Follow Climate Change: Climate News Use and Attitudes in Eight Countries,” Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism at the University of Oxford, December 2022.

Emanuel, Kerry, What We Know About Climate Change, MIT Press, 2018.

Hansen et al, “Global warming in the pipeline,” Oxford Open Climate Change, Volume 3, Issue 1, 2023.

Stephens, Bret, “The Mask Mandates Did Nothing. Will Any Lessons Be Learned?” New York Times, 21st February 2023.

If you liked this essay, you might enjoy these related pieces:

Nightswimming

My arms make arcing breaststrokes in tepid turquoise water, slicing through its smooth thickness which envelops my skin like silk. I bob down 15 feet or so to the seabed, where the water turns darker blue, cold, invigorating. I pinch my nose as I twist my body to look upwards at the light above. As a child I feared the salt stingi…

Nobody Understands Climate: Kerry Emanuel and Hurricanes

In his essay, What They Don’t Tell You About Hurricanes, the late Philip Gerard provides a step-by-step emotional account of the far-reaching implications of experiencing an extreme weather event. He writes about the nervous anticipation triggered when the weather warnings are issued for his C…