Nobody Understands Climate: Kerry Emanuel and Hurricanes

The Anthropocene Essay: Part One of Three

In his essay, What They Don’t Tell You About Hurricanes, the late Philip Gerard provides a step-by-step emotional account of the far-reaching implications of experiencing an extreme weather event. He writes about the nervous anticipation triggered when the weather warnings are issued for his Cape Fear community; the uncertainty as to whether and how to take mitigating measures to protect life and property; the dread that the full force of the hurricane will hit North Carolina’s shores at high tide; the constant, anxious, checking for updates as the clock counts down to impact – needing to know, “When, How Hard, How Long: the trigonometry of catastrophe.”

Through describing the indiscriminate, unfair and gruesome destruction of a hurricane, Gerard highlights the precariousness of human existence. He shows us that behind the data and statistics of climate change, beyond the aspirational political declarations and policy prescriptions, there lies a very human reality: a devastating personal toll, that continues to be felt long after an extreme climatic event hits. It is not an incident, but a protracted event with a domino effect of longer-term repercussions.

Gerard was writing about Hurricane Fran, which tore through nine eastern US states in September 1996. North Carolina bore the brunt of it, with 14 people killed and more than $2 billion in damage caused. When Gerard wrote the essay in the late 1990s, climate models predicted today’s increasingly common extreme weather events as having outlier probability. In other words, the potential ferocity of what we are witnessing today was foreseen, but the increased frequency of occurrence was considered far less likely to materialise back then. As I will come on to discuss, we are yet to adequately combine the modelling with policy responses to the new realities.

Gerard didn’t live to witness North Carolina’s latest encounter with a devastating hurricane, which came in the form of Hurricane Helene last September. Helene was quickly followed by Milton, adding two more to the list of major hurricanes of the 21st century which have been, to date, smashing all kinds of records for different measures. They are just the latest in a growing list of adverse weather events linked to climatic change.

As I will touch on further down, hurricanes become more severe as temperature warms … and 2024 was the hottest recorded year in history, breaking the record set the previous year. Hurricanes bring greater rainfall and add to a wider picture of water volatility, effecting different places in different ways – floods and droughts are both increasing to devastating effect. The risk of food shortages and price rises increase as extreme weather linked to climate change creates lower agricultural yields. Climate change may not (yet) have directly triggered a war, but it is certainly triggering the conditions which could lead to armed conflict.

“I’m more comfortable with nuclear and advanced production,” I tell him.

“I’ve been working on that with Jacopo for the past couple of years,” I add. He doesn’t volunteer a response.

“So, I can make that argument, but I need more help on the first part,” I continue, hoping to elicit a reply. Still no solution is offered.

“I don’t understand climate,” I finally confess.

“Nobody understands climate,” he says – at which he, Jacopo and I all smile. He suggests some background reading for me to do. He knows I’ve glanced over his climate primer paper, because I’ve questioned him on it before for a podcast panel discussion that I hosted with him and Jacopo. But he isn’t going to let me off the hook of doing my homework properly.

After many decades as professor of atmospheric science at UCLA and MIT, Kerry Emanuel has now retired from teaching to focus on research and ‘doing’ more science. His previous work has already transformed our understanding of climate change and its costs, from hypothetical cause and effect to grounded reality, not least through providing evidence that oceanic storms have become more powerful as a result of higher water temperatures, caused by increased atmospheric greenhouse gases. He flew in from Japan yesterday and has another book manuscript he’s working on, on top of a host of other commitments. Such is the life of an MIT Professor Emeritus, who just happens to be a world authority on meteorology and climate science.

He shows a degree of patience with my relative ignorance, but then he’s accustomed to it. Virtually nobody can discuss these issues with him, on his level. He humours me on some of my basic misunderstandings. I ask him about the reported levelling-off of greenhouse gas emissions and why, despite this, the observable reality shows that global temperature increases and the frequency of extreme weather events are accelerating. What’s going on?

“If emissions were merely levelling off, there would still be rapid growth in greenhouse gas concentrations,” he explains. “If they were to stop altogether, greenhouse gas concentrations would not rise further, but would take hundreds of years for concentrations to fall appreciably.”

I ask about some drafting I’ve put together on exceeding the 1.5 degrees Celsius temperature increase limit and whether so-called climate tipping points can be expected much sooner than expected. Again, he enlightens me. “This is problematic. First, there is no particular threshold beyond which tipping points can be expected, and secondly, tipping points are conjecture, so that we cannot predict them at all. A phrase like ‘increasing the risk of tipping points’ might be justified.”

Undeterred, I go away and read further articles and reports, discovering that I know more about the subject than I’d given myself credit for. The challenge is less one of comprehension, but more of distilling the complex information into a digestible format. Eventually, I decide to give myself a break and not even attempt to provide a sophisticated explanation of climate science. I’ll leave that to those who are qualified to do so. On that note, I highly recommend reading Kerry’s short book, What We Know About Climate Change. It’s the best outline of the issue I’ve read, and it takes only a few hours to digest.

Instead, here I’ll briefly share my understanding of what the issue is, in a nutshell. As I say, I’m not completely ignorant on the topic of climate change. However, like many of us, I do find that it’s easy to feel confused, overwhelmed and even detached from the story of climate change. The science explaining it can seem impenetrable, the back and forth between different scientists and activists on points of technical detail can feel abstract and removed from the reality of our daily lives – and sometimes even from the reality of dramatic climate events we increasingly see and hear about in our news media. The politics of climate change is beyond frustrating, showcasing so much of what is wrong with contemporary societal discourse.

Opinion polling shows that, irrespective of our political outlook, geographic location or identity, most of us care very deeply about the environment and are concerned about climate change. We want our governments, public institutions and private corporations to take the necessary action to mitigate and combat the worse effects of climate change. We want to play our part … we just don’t know exactly what that is. We want solutions to be found, but we hear conflicting information about what they are. World leaders don’t seem to be able to make progress. How many of us really care what comes out of United Nations COP summits anymore? The acronym itself is problematic. It stands for “Conference of the Parties” – hardly translatable to the common vernacular most of us connect with. They could just call it “junket” and be done with it.

So, what is the nutshell I’ve promised? Well, first the distinction should be drawn between post-industrial revolution climate change and the long-term fluctuations in weather patterns that would be expected irrespective of any human activity. Earth is 4.5 billion years old and throughout its existence, its climate has not been stable but rather has changed in a number of different ways.

One (but not the only) example of climate change is witnessed through the different glacial cycles which have played out in segments of around one-hundred thousand years. To look at Planet Earth from space would, at various times, show changes from a completely white ball when Earth’s surface was entirely covered with ice, to a blue and green mix when there was no ice, not even on the poles – and everything in between. Sea levels have risen and fallen dramatically throughout the ages, as have global average temperatures. Such variation has happened for different reasons and on different timescales. Kerry explains to me: “The gradual decline of global temperature over the past 100 million years or so is a much greater change, but over a much longer period.”

We know this in large part thanks to the study of climate records by scientists in the field of Paleoclimatology. Natural ‘proxy’ records of weather patterns, covering millions of years, are kept in such things as tree rings, fossils, layers of ice, coral or the patterns of layers of sediment in rocks formed by glaciers. Even the location of such rocks serves as evidence of past glacial periods in a particular location.

Here I could regurgitate information, on which I am no expert, to try to explain why all of this happens the way it does. I could try to explain how the changing tilt of our planet, or variations in Earth’s orbiting of the Sun, have been among the many different drivers for our planet’s historical climatic variations and instability. For ease, it is better to direct anyone seeking more detailed explanation to go and read Kerry’s aforementioned book. There are also a number of useful resources available on the internet, including the US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) website. I also recommend the fine work of the good folks at MIT, who turned Kerry’s climate primer paper into a Webby Award-winning website.

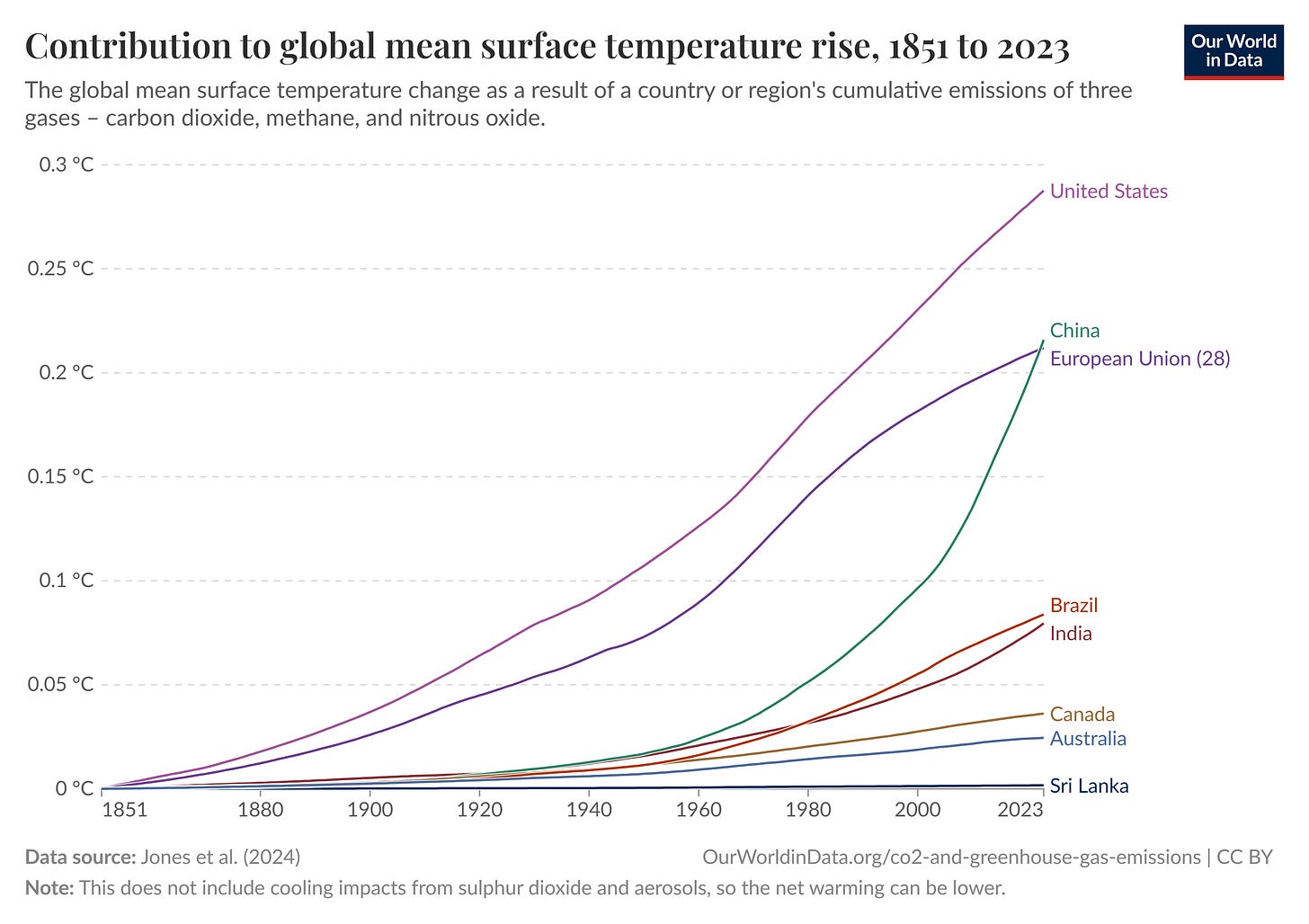

The key area to focus on is the more recent acceleration in global mean temperatures caused by human activity. For decades now we have been witnessing, in the data, the rise in greenhouse gasses that trap heat, leading to warmer temperatures recorded on the surface of the Earth. The leading greenhouse gasses are: carbon dioxide, methane, chlorofluorocarbons, nitrous oxide and ozone. Carbon dioxide (CO2) content started to rise in the late 19th century. This can be inferred from bubbles of atmosphere trapped in ice and detected in ice cores.

In 1958 we started directly measuring CO2 from the observatory on Mauna Loa, Hawaii. Since then, we have witnessed the increase of CO2 in our atmosphere at an ever-accelerating rate – a sharp uptick that is higher than the amount that can be captured by Earth’s natural carbon cycle. This has largely (around 70 – 80 percent today) come from burning fossil fuels such as oil and coal, to power our lives: our homes, industries and transport systems. Agriculture, manufacture of concrete and changing land-use patterns (including deforestation) have also made significant contributions.

The pivotal change started more than 200 years ago with the industrial revolution, as evidenced by the sharp increase in greenhouse gases and sulphate aerosols. However, the impact can be witnessed dramatically in the data from the middle of the last century.

Hence the subheading of this essay; some are dubbing this post-1950 period “The Anthropocene” – namely the era of human activity having a significant impact on Earth’s climate, weather, geology, landscape and ecosystems. The result is what we commonly term climate change, and refers to the increase in global average temperature (global warming) and the resulting effects this has on Earth’s climate system, including the increase in weather volatility and extreme meteorological events.

Across the world for more than a century, in weather stations on land and at sea, daily high and low temperature recordings have shown that Earth’s average surface temperature has increased by about 1 degree Celsius since 1880. This temperature increase directly correlates with increased levels of CO2 recorded in Earth’s atmosphere over the same period.

Unless it is offset in equal measure by something that has a cooling effect, increasing CO2 will lead to warmer surface temperatures. Since 1800, the amount of CO2 in the atmosphere has increased from about 280 parts per million (ppm) to more than 410 ppm today.

Earth’s surface temperature increase is leading to a reduction in inland and sea ice, most notably the reduction in ice mass in the Antarctic and Greenland. Given that oceans absorb most of the excess heat from the air, they are further exacerbating the ice decline through rising water temperatures towards the surface. The warmer water is permeating deeper and harmfully affecting marine ecosystems. There is more to the physics of ice, but the substantive point is that big glacier and ice sheet melting is raising sea levels, at an increasing rate.

Our large cities and major population centres tend to be on coastal and estuary locations. Hundreds of millions of people, from downtown Manhattan to Osaka are at risk of seeing their homes submerged from flooding, or hit by the increased storm activity that results from higher sea levels. Mountain ranges including the Himalayas, Andes and Alps are witnessing the decline of glaciers, which further adds to the overall problem.

… to be continued next week in Part Two: “Nobody Understands Climate: Can We Trust the Science?”

References:

Emanuel, Kerry. (2018). What We Know About Climate Change, MIT Press

Gerard, Philip. “What They Don’t Tell You About Hurricanes.” Creative Nonfiction, no. 11 (1998): 100–109

Some dialogue above taken from a conversation I had with Kerry Emanuel and Jacopo Buongiorno to discuss a draft book manuscript: “Gridlocked: why the 21st century is broken and how to fix it.”

If you liked this essay, you might enjoy these related pieces:

Nightswimming

My arms make arcing breaststrokes in tepid turquoise water, slicing through its smooth thickness which envelops my skin like silk. I bob down 15 feet or so to the seabed, where the water turns darker blue, cold, invigorating. I pinch my nose as I twist my body to look upwards at the light above. As a child I feared the salt stingi…

We Need New Stories

Humanity is at an inflection point, seemingly unable to cut through division and societal angst. A toxic combination of demagoguery and oligarchy is challenging the democratic norms many of us have taken for granted throughout our lives.